Timshel...

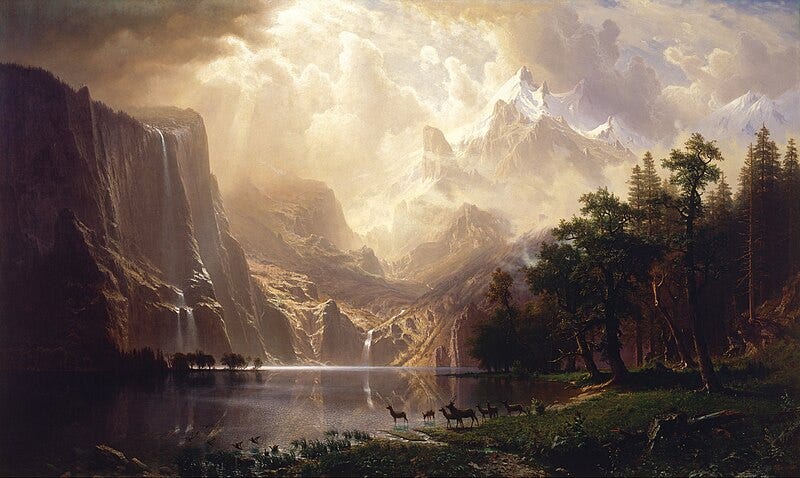

Seven letters near the front of a dusty book, hidden away from the prying eyes of the world, forgotten. Once in a while, the frail spine of the tome is bent gently open, the ivory pages caressed by the the touch of a finger. As the words are brought alive, the audience of starry-eyed children tremble before the idea of all the Heavens and the Earth, created by one being, almighty, the one true God.

How many generations of children have experienced this feeling? A pinch at our extremities, in anticipation of such great knowledge, a universal knowledge. It slowly swells like a symphony, invading our entire being, burrowing deeper into the soul than we had ever been before, inspiring such awe that we had no choice but to believe it. After all, if this God had created such immense beauty in the natural world, and our parents, who in effect were living Gods, what powers did he not possess? What choice did we have but to praise him?

As we grew and our education progressed, we turned to science and fact. Our own Enlightenment, of sorts. We learned of Newton and of Darwin, the scientific origins of the universe, and of emigration from Africa. We were now beings of reason…

In our spiritual needs, we turned to literature for answers — from Sophocles to Shakespeare to Saint-Exupéry, each work is a voyage into the essence of humanity. These authors, among the greatest to have ever graced humanity, all do one thing well. From sonnets to tragedy, they meticulously craft stories that exude the cravings of the human soul.

John Steinbeck’s East of Eden is, in this way, radically conventional. He develops a multigenerational family narrative, intricate storylines, and the landscape of the Salinas Valley to communicate a single idea, reflected in a single word: Timshel.

Steinbeck challenges us to go back to the very beginning, to the first book that many of us experience, to that first moment of utter awe, to our first adventure into ourselves and our souls. Back not only to our creation, but the creation of the world.

The story of Genesis shows that since Creation, we have been human. Human in the physical sense, yes, but more importantly, human in our desire. As children, we were told that Eve and Adam ate from the forbidden fruit and were banished from Eden, and that was the origin of our sin. We were all sinners, descended from them — this was inherently human. It was our commandment to rid that sin from our lives.

Yet, in the first truly human environment, banished from Paradise, we fall to our natural state — sinfulness. The fourth chapter in Genesis recounts the murder of Abel by his brother Cain. A cautionary tale of the power of envy in our lives on the surface, Steinbeck examines a small detail that penetrates to the very heart of the Abrahamic religions. The lynchpin of the worldview of billions of people around the world is the translation of a single word.

Through history, there have been countless translations of the Old Testament, with varying intentions. Some catered simpler translations for the masses, while others sought to translate older, Greek and Latin versions as faithfully as possible. Steinbeck returns to the original Hebrew, examining the sixteen verses of this story from Genesis, and finds disaccord on the meaning of ‘timshel’.

Speaking with Cain, God references humanity triumphing over sin. As Lee, the protagonist’s right-hand man, explains it:

Lee’s hand shook as he filled the delicate cups. He drank his down in one gulp. “Don’t you see?” he cried. “The American Standard translation orders men to triumph over sin, and you can call sin ignorance. The King James translation makes a promise in ‘Thou shalt,’ meaning that men will surely triumph over sin.

But the Hebrew word, the word timshel — ‘Thou mayest’ — that gives a choice. It might be the most important word in the world. That says the way is open. That throws it right back on a man.

For if ‘Thou mayest’ — it is also true that ‘Thou mayest not.’

Later…

“And I feel that I am a man. And I feel that a man is a very important thing — maybe more important than a star. This is not theology. I have no bent toward gods. But I have a new love for that glittering instrument, the human soul. It is a lovely and unique thing in the universe. It is always attacked and never destroyed — because ‘Thou mayest.’”

This is everything. Everything it means to be human, neatly summed up in a few pages. It justifies the struggle, the effort, the anxiety, the nervousness, the pain, and the terror. We have power over our own lives, over our circumstances, no matter how desperate they may seem. Nothing is guaranteed, nor are we commanded to any action by some other being. We are entirely our own.

I’ve often wondered how to reconcile philosophies. One man, whom I hold in great respect, says so, and the other contradicts him. They both seem reasonable, and in practice, they both have their merits. How should I decide?

East of Eden taught me to think about the Bible in a new light — not simply as a religious foundation for the Christian religion, but a philosophical text in its own right. There is spiritual truth, even if one chooses not to accept it as religious truth.

Spiritually, a good philosophy is one that allows for individual’s influence on their own lives.

Whether that manifestation is found in the Meditations, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, or Siddhartha, the fundamental truth laid out in the Bible is reflected in all of these works. While philosophies may butt heads in the intricacies, this fundamental truth remains. And if it is not there, well, I ought to think twice about putting it into practice.

The reality is that if one has truly given careful thought to this aspect of their lives, we would find that they wouldn’t describe themselves as a follower of Descartes or Derrida, but as a creator of a new, deeply personal set of virtues and morals, borrowing from others but adding themselves into the question. This is what we could call an ever-changing, immortal ‘self-philosophy’, existing alongside the human spirit from birth until death.

Even if we aren’t conscious of it, it exists, somewhere below the surface. The more you read, learn, and experience, the further it develops. If nothing else, remember that it always exists within, and that you have the power to shape it, just as it shapes you.

My name is Alexander Yevchenko. I’m 18 years old, and a Morehead-Cain Scholar at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. If you’d like to keep up with me, I’m most active on X, @ayevch. If you enjoyed this reflection or just want to send a message, send me an email: alexanderyevchenko@gmail.com.